One of Australia’s most decorated and longest serving military commanders has revealed he will donate his brain to research, as the Australian Defence Force grapples with the impact of blast exposure on soldiers’ cognitive health.

In the past two weeks, more than 200 current and former service personnel have pledged their brains to the Australian Veterans Brain Bank (AVBB), after the ABC reported growing evidence of a link between mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) associated with blast exposure and poor mental health and suicide.

Repatriation Commissioner Khalil Fegan, who served in the military for 34 years and led troops in Afghanistan and Iraq, was among the first to sign up to the AVBB when it opened last year.

During his service he was routinely exposed to thousands of blasts from heavy weaponry and explosions, but said he never considered the impact it may have had on his brain.

“I wasn’t thinking about any potential damage that exposure to blast was doing at all. It was just something that I wasn’t attuned to,” he said.

“At the time, if I fired 500 rounds in a day, I’d go home disappointed I didn’t fire 1,000, and it was just something that I just wouldn’t have considered.

Kahlil Fegan says during his decades long career, the operational environment evolved, and training with heavy artillery ramped up for operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. (ABC News: Department of Defence)

“There clearly needs to be more research in this area to understand why there could be cognitive decline in some veterans.”

For Mr Fegan, it’s a deeply personal issue. He watched his father, a Vietnam veteran, rapidly deteriorate from younger onset dementia.

“We went from having an immensely intelligent, engaged father to someone who couldn’t string two words together and died a shadow of a man,” he said.

“We don’t know if dad died as a result of something that was hereditary, or something that was naturally acquired, or something that is attributed to his service … we just don’t know.

“We didn’t know about the veteran brain bank … when he passed away, so we’ll probably never know whether there was an underlying physical injury.

“It’s just so evident that more work needs to be done in this space.”

Veterans brain bank experiences surge in donations

Researchers are still learning about how blast exposure impacts the brain and it is only when the brain is dissected after death that they can see the microscopic damage.

Dozens of veterans told an ABC investigation last month they had experienced symptoms including short-term memory loss, headaches, depression, tinnitus, hearing loss and uncharacteristic sudden bursts of rage which they attributed to their repeated exposure to blast overpressure.

Researchers analysing hundreds of veterans’ brains in the US have found new kinds of scarring on the surface of the brain linked to repeated blast exposure, causing a constellation of symptoms.

Established last year, the AVBB only has one brain to study so far.

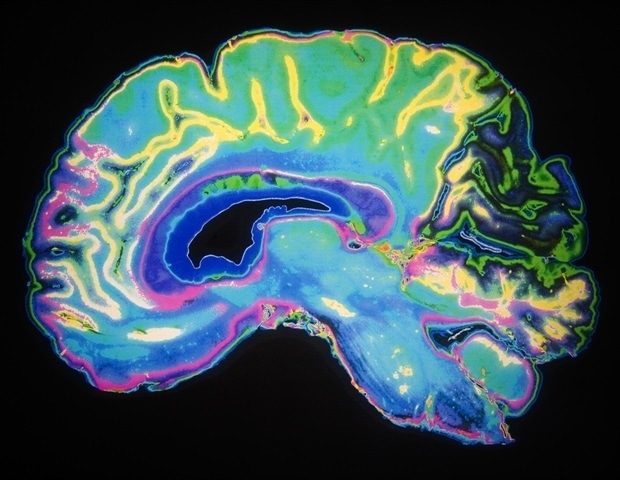

“The pathologies that we’re looking at predominantly are occurring at that microscopic level,” director and neuropathologist Dr Michael Buckland said.

“While a scan can give you an overall indication of brain health, or if the brain is shrinking, or if you had a stroke or a bleed into the brain, if you want to dissect the exact type of degenerative brain disease that someone might be suffering from, that still very heavily relies on examination under the microscope.”

The number of future/prospective donors has risen from 100 to 300 in the past fortnight after ex-special forces commando Paul Dunbavin spoke publicly about his struggles with memory loss linked to mTBI.

“Remarkably, 200 of those people have signed up in the last week or so since the 7.30 report went to air,” he said.

Loading…

Luke, not his real name, served alongside Mr Dunbavin in the special forces.

When he saw his friend speaking about his struggles, he signed up too.

He said throughout his 16-year military career he was exposed to thousands of blasts — in training and in the field as a breacher with the special forces.

In Afghanistan, he spent his time busting into Taliban-run heroin labs.

“We would never go through the door, because there were always IEDs [improvised explosive devices], we would always go through the wall,” he said.

“We would set charges on the wall and blow through the wall [and then] we’d go in, there’d be heroin presses, barrels full of chemicals, and then we’d set our charges and destroy those heroin labs so they couldn’t be used for the production of heroin, which funded the Taliban.”

Towards the end of his military career, when he was supervising demolition practice in Australia, he started to notice the same symptoms his mate had spoken about.

“I was having headaches that were just completely incapacitating and my memory was very bad,” he said.

“I would walk into a shop to buy something, I’d buy something else, go home and realise I didn’t get what I’d actually gone to buy.

“My recall was very, very poor for basic things. I could still remember detailed things from years ago, but then my short-term memory was just atrocious.”

There would be nights when his headaches were so bad he opted to sleep at work, because driving home was too much to bear.

“I didn’t feel confident to drive so that was pretty much when I said, ‘okay, there’s something not quite right here’,” he said.

By that time, Luke said he was deemed unfit for deployment. He left the military and got some medical attention.

He ended up being part of a University of Queensland study, which was looking into mild traumatic brain injuries and PTSD.

“I went up there and spoke to some really lovely people who put me to MRI machines, basically got me solving puzzles while tracking my brain chemistry and what happens and when I got out of that, they basically said, ‘yeah, you have a traumatic brain injury and things aren’t working’,” he said.

Call for ADF to reconsider safe blast exposure levels

Last month the US deputy defense secretary issued a memo acknowledging personnel were experiencing “possible adverse effects on brain health and cognitive performance” from exposure to blast overpressure (BOP).

Repatriation Commissioner Khalil Feegan said it was time the ADF reconsidered what level of blast troops were exposed to.

“Based on what we now suspect, I think it’s worth revisiting the protections and mitigations we’ve got in place,” he said.

“Based on what we understood at the time, we mitigated to the best of our abilities, through the wearing of hearing protection and other protective measures.

Researchers at the Veteran’s Brain Bank dissect the brain and examine it under the microscope to see details that cannot be picked up by scans. (ABC News: Elise Worthington)

“But now if there is a suspicion, then we need to reconsider, to ensure that we’re protecting our people as best as possible, but still training to be able to do the government’s bidding on operations when we’re called upon to do so.”

The ADF previously told the ABC it was doing research and trials relating to blast exposure and was taking a “precautionary approach”.

It said internal guidance was updated last year to include measures to minimise exposure to repeated low-level blast overpressure where possible.

“Existing work, health and safety systems are employed to manage and minimise exposure to repeated low-level blast exposure” an ADF spokesperson said.

The Royal Commission into Defence and Veteran Suicide is due to hand down its final report on Monday.

In his closing statement, commissioner James Douglas, KC, said it would recommend the establishment of an independent permanent body to “not only monitor the implementation of our recommendations, but also to keep a close eye on the problem [of suicide] as a whole”.

“One issue that’s been canvassed in the press recently is about traumatic brain injury. We’ve had evidence about that, but that’s an area of continuing inquiry, and it may well cast different light on the issues we’ve examined into the future,” he said.

More than 300 people have now pledged to donate their brains. (ABC News: Elise Worthington)

Former Special Forces commando Luke is closely watching the ADF’s next moves and tracking the emerging research into mTBI.

He has cut back on drinking, watches his diet and said it’s his family and connection to the community that has kept him alive.

“I think we as a society, particularly the government and military, have a responsibility to take steps to ensure that people are happy and healthy post service,” he said.

“We have a responsibility to make sure we look after people.”

Khalil Feegan wants to see more veterans sign up too.

“This pledge won’t change anything for you after you’ve donated your brain, but it might be absolutely fundamentally life changing for a future generation of veterans,” he said.

“And so I really, I really encourage veterans to continue to do it.”

Loading…