Anita knows she has an uncommon profession. She regularly visits sex shops, talks to sex workers — words like vulva, erection and orgasm are all part of a productive day on the job.

Working as an occupational therapist, Anita specialises in helping people living with illness or disability with their sex lives.

The Melbourne-based health worker was struggling to teach some of her clients about the vulva. She had a puppet which was “fantastic” but not anatomically correct.

She also had line drawings but they were useless for her clients who are blind.

All Anita wanted was an anatomically correct 3D model of the female genitals.

“At that point I was like, ‘Oh, there’s nothing out there. Well, I suppose we will just have to make it.'”

She embarked on a mission to make an accurate model but found some questions about anatomy were difficult to answer – particularly about the clitoris.

So what is the clitoris?

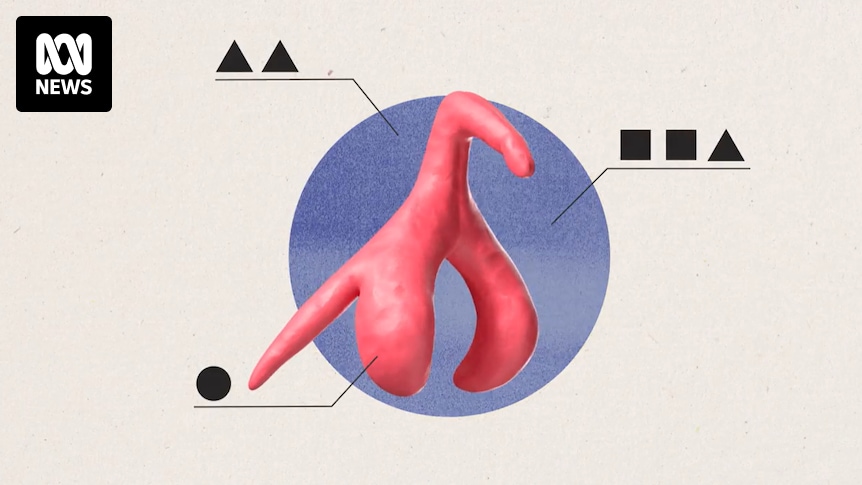

The clitoris is an internal and external organ and the part of the female genital anatomy responsible for orgasms. Thousands of nerve endings make a wishbone shape – wrapping around the vagina — and its size is typically 9x9cm.

Just like the male genitals, when the female genitals are aroused, the clitoris becomes engorged.

“I think that’s the first thing people think: well, surely it’s not that big,” medical anthropologist and midwife Dr Suzanne Belton said.

“And I think it’s because we’ve all been told that the clitoris is very small and it’s hard to find.”

The organ has had a complicated relationship with Western medicine. In the medieval witch hunting guide “Malleus Maleficarum” it was referred to as “the devil’s teat”.

In the 1500s renowned physician Andreas Vesalius called it a “new and useless part”.

In the 1600s scientists began studying the organ in detail – with Dutch anatomist Regnier De Graaf publishing an anatomical depiction of the clitoris.

Centuries later, in 1948, anatomical representations of the clitoris disappeared from the 25th edition of Gray’s Anatomy.

“It’s very curious, what you see is usually men of science doing the dissections and writing about the clitoris, and then you see this knowledge lost,” Dr Belton explains.

“It’s just part of a woman’s body that you should understand. But it also has a very special function, right? I mean, it’s for pleasure and it causes orgasms. And that seems a significant function for wellbeing.”

Focus has always been on men, not women

This gap in knowledge was noticed by Professor Helen O’Connell, president of the Urological Society ANZ, when she was in medical school. She saw that authors would describe in “intense detail” the anatomy of the male and add addendums on the differences in women.

“Whether you’re a general practitioner or a surgeon, or a gynaecologist, or gynaecologic surgeon, knowing what’s there makes, I would think, a huge difference to the way you operate and the way you think of potential therapies or operations that could be devised in the future,” she said.

“There are nerves that run under the pubic bone. And if they’re directly impacted by surgery, that’s potentially going to make the clitoris numb or even painful with effects on a woman’s pleasure, but also even her willingness to to participate in intimate activities.”

This vexxed Professor O’Connell. After becoming Australia’s first female urologist, she led the first comprehensive anatomical study on the clitoris in 1998, and examined it further under MRI in 2005.

“We were able to bring modern science to a complete focus on female genital anatomy,” she said.

Her work better informed doctors and surgeons of the location of nerves and how the clitoris interacts with other parts of the female genital anatomy. It has also formed part of a movement to advance knowledge on the organ – both medically and culturally.

International Cliteratti

Determined to make her model accurate, Anita Brown-Major reached out to the experts – including Professor O’Connell and Dr Belton.

“There were lots of questions that I just couldn’t find as an occupational therapist,” she said.

“Questions like, how does the clitoris get erect? Do the glands actually stand up or stand down, or not at all?” Ms Brown-Major said.

A network of scientists and healthcare professionals around the world formed – including from Australia, the US, France and Sweden – many making their own models. The group swapped notes on their research and experiences dealing with this misunderstood organ.

“We just support each other and learn from each other,” Dr Belton, who has made her own 1:1 model of the clitoris with Professor O’Connell and Dr Ea Mulligan, said.

In April 2022, the International Cliteratti developed when the women had their first Zoom meeting.

“I was so excited when we had our first meeting, and to walk out and go, ‘There’s other people who are excited about this work,'” Ms Brown-Major said.

With the support of the group, her colleagues and the RMIT Industrial Design Program, Ms Brown-Major launched her own model – Cliterate — a pull-apart sphere that accurately shows the relationship between the clitoris, vulva and pelvis.

“What keeps me going is trying to educate and empower people with knowledge,” she said.

Watch 7.30, Mondays to Thursdays 7:30pm on ABC iview and ABC TV

Posted , updated