What should be a new era of medical board governance has begun with what looks more like a finger to the eye of the U.S. Supreme Court. On May 22, a federal district judge in Austin, Texas heard arguments to determine whether a rule adopted earlier in the month by the Texas Medical Board should take effect on June 3. No decision on a temporary restraining order has yet been issued, but the hearing offered a preview of litigation likely to arise under federal antitrust law as it was recently clarified by the nine justices.

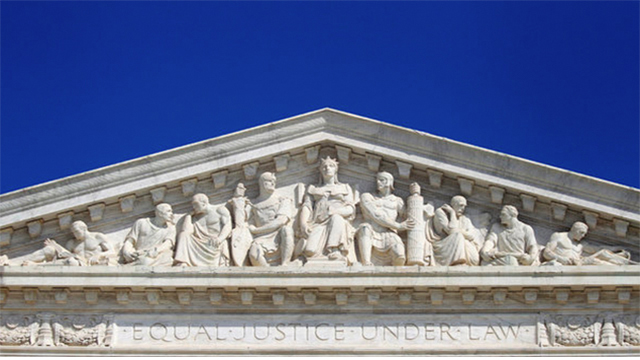

In February 2015, the Supreme Court decided North Carolina State Board of Dental Examiners v. Federal Trade Commission, a case involving “cease and desist letters” sent to non-dentist teeth whitening businesses. By a 6-3 vote, the Court subjected professional licensing boards with a majority of members from the regulated profession to antitrust lawsuits unless they are “actively supervised” by the state itself.

The dispute in Austin pre-dates the Supreme Court’s ruling. For several years, the Texas Medical Board has been in litigation with Teladoc, a Dallas-based company that contracts with licensed Texas physicians to provide telephonic consultations to patients in the state. Teladoc physicians sometimes prescribe medications during those sessions, a practice that the Texas Medical Board has attempted to eliminate by an increasingly stringent set of interpretations and amendments to its longstanding Rule 190.8, which quite reasonably prohibits prescribing unless a physician-patient relationship has been established.

Each of these actions was challenged by Teladoc under state administrative law, including the Board’s adoption in January of an “emergency rule” that was stayed by the courts for lack of a demonstrated emergency. To settle the issue, the Board amended the Rule at its May meeting to require an in-person physical examination by the physician or presentation of the patient to the physician by another health professional using a high-resolution video connection. Because 12 of the Board’s 19 members are licensed physicians, and the Board’s action is not “actively supervised,” the new Rule 190.8 fits squarely within North Carolina State Board and is subject to review under the federal antitrust laws.

At the hearing, however, the fact that the Teladoc litigation had morphed from administrative law to antitrust law was lost on the Texas Medical Board’s lawyers. Based on the case it presented, the Attorney General’s office seemed unclear on the concept of competition being unlawfully hindered by licensing board action. The Assistant Attorney General arguing on behalf of the Board brushed aside Teladoc’s challenge on the ground that “practitioners are always looking for new avenues of attack on regulation,” and even claimed it was “kind of a distortion to be talking ‘business’” — entirely missing the point that established practitioners were being accused of abusing their regulatory privileges to insulate their existing business models from competition.

Indeed, the language of competition seemed alien to the Board’s attorney, even though the Attorney General’s office employs an expert cadre of antitrust litigators in other matters. He spoke mainly in terms familiar to the profession, such as “standard of care” and “medically necessary,” and offered his own impromptu opinions on what can happen if physicians aren’t forced to take every precaution. More worrisomely, he cited state Medicaid coverage rules as validating the Board’s restrictions on private physician practice (they don’t), and argued that a medical restraint of trade cannot be “unreasonable” and therefore prohibited by the Sherman Act unless no reasonable physician would support it (it can).

Whether or not the judge issues a preliminary injunction in the Teladoc case, similar challenges to state licensing board action are likely to proliferate. The Supreme Court understood this when it decided North Carolina State Board, and the Texas Medical Board’s apparent obliviousness to competition proves that the Court made the right call and that antitrust oversight is needed.

Looking Forward

Over the next months to years, we can expect several important questions to be raised and debated in antitrust litigation involving state licensing boards. Are all rules at risk, or only those that demonstrably favor the interests of the active market participants who control the board? Drawing on the Supreme Court’s 1999 ruling in the California Dental Association case, must a plaintiff prove a complete case under the “rule of reason” or may a court condemn a licensing board’s practice after only a “quick look”? What procompetitive benefits may be asserted in defense of a challenged rule beyond the established profession’s views regarding quality or safety? Can “consumer confidence” from the existence of comprehensive professional regulation be considered a procompetitive benefit, even if that regulation appears excessive or unjustified?

As more private plaintiffs sue state licensing boards under the federal antitrust laws, other novel issues will arise. To his credit, the Texas Assistant Attorney General identified some of these in his presentation. Does state sovereign immunity under the 11th Amendment to the Constitution constrain or prohibit suits for injunctions or damages involving bona fide state agencies that the federal antitrust laws now treat as private parties? (Teladoc sued the Board as a whole, and also sued each of the Board members who voted in favor of the new rule both as individuals and in their official capacities.) How will plaintiffs prove “antitrust injury” when action is being taken by a licensing board rather than by entities with whom the plaintiff is doing or wants to do business? Will these legal hurdles be easier to surmount when a board has adopted a blanket rule involving many potential competitors, as opposed to taking disciplinary action against a single competitor?

Most importantly, how should states “actively supervise” professional licensing boards in order to protect them and their members from repeated suit? Should states provide for direct legislative or executive branch review and validation of formal board action on a regular basis? Might states work together to develop a uniform state law setting forth supervisory “best practices” that each state could adopt after modification to suit its individual circumstances and philosophies? Should Congress intervene, as it did in the late 1980’s after the Supreme Court ruled that hospital medical staffs were not immune from antitrust liability?

In the near term, federal courts hearing antitrust challenges will be asking state licensing boards some unfamiliar and uncomfortable questions about the evidence supporting their professional judgments. Licensing boards are often loath to interfere with the judgment of their mainstream licensees. Texas Rule 190.8, for example, did not specify exactly how a physician-patient relationship must be established until Teladoc’s practices became known, and the Board still inexplicably allows “on-call” physicians covering for patients’ regular physicians to prescribe medication after a phone call. As the judge in Austin observed, there has to be “something more than ‘we’re doctors, trust us.’”

Only the Texas Medical Board knows why it adopted this particular rule at this particular time. It seems doubtful that preventing competition was its major goal. On the other hand, the rule doesn’t seem necessary to protect patients either. Like many legal disputes, the years-long battle between Teladoc and the Board probably has a lot to do with strong personalities and entrenched positions. But in a health care system desperately in need of access, efficiency, and innovation, how it plays out will matter to us all.

SOURCE: Health Affairs Blog – Read entire story here.