Truth in the nutrition sciences has been critically advanced by the writings of investigative journalists, who often arrive at their chosen topics indirectly.

Two stellar recent examples are Gary Taubes and Nina Teicholz, whose seminal works have forever changed the scope and direction of the global debate about “healthy” nutrition. Taubes and Teicholz have shown that the modern nutrition sciences are directed by forces more likely to cause illness than to promote health. Their contributions pose the fundamental question: Why does it take investigative journalists—mainly self-taught in the science of nutrition—to expose what the rest of the world, diet professionals especially, apparently cannot see?

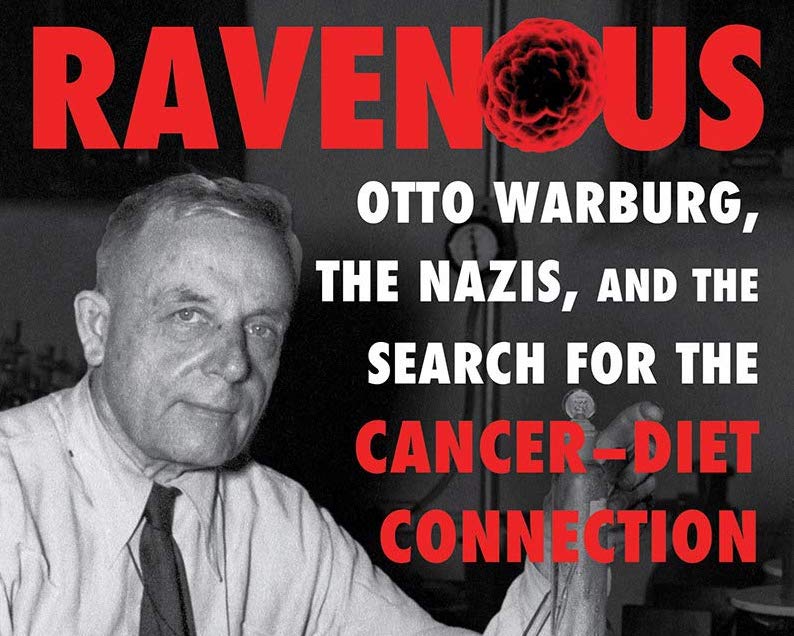

To the seminal, highly influential works of Taubes and Teicholz, we must now add a third, Ravenous, by investigative journalist Sam Apple. Ravenous completes a trilogy of revolutionary contributions from these gifted writers.

The central story in Ravenous is the biography of the German professor Otto Warburg, one of the most influential biochemists of all time. Warburg was a huge personality. A colleague once said that on a scale of arrogance from 1-10, Warburg rated 20. Many of his colleagues considered Warburg to be God-like—which poses a colossal challenge for a writer daring to attempt the biography of such a deity. Apple proves he is up to the task by producing a flawlessly researched, exquisitely constructed, and magnificently narrated book that builds to a thrilling climax.

Ravenous is storytelling at its very best. Warburg believed he was destined to discover the singular reason why all cancers develop. Apple shows how Warburg’s ideas, first pioneered nearly a century ago, and then discounted, are once more gaining traction.

The Prime Cause of Cancer

Warburg was fortunate to begin his specialized research in Berlin at a time when brilliant German scientists—many, like Warburg, of Jewish heritage—were creating entirely new scientific fields. Warburg’s breakthrough arrived when he developed new techniques to measure the breathing of cancer cells. To his great surprise, Warburg found that rapidly growing cancer cells were not relying on oxygen for fuel, as do normal cells. Instead, the cancer cells were converting glucose to lactic acid, extracting energy without oxygen—a more primitive process, known as fermentation. In time, Warburg’s unexpected discovery became known as “the Warburg effect.”

Warburg concluded, perhaps too grandly, that he had discovered the essential biochemical hallmark of all forms of cancer. “Cancer, above all other diseases, has countless secondary causes,” Warburg wrote. “But, even for cancer, there is only one prime cause. Summarized in a few words, the prime cause of cancer is the replacement of the respiration of oxygen in normal body cells by a fermentation of sugar.”

Warburg was aware that another extraordinary scientist, Frenchman Louis Pasteur, had described a similar phenomenon—which Warburg himself later labeled “the Pasteur Effect.” Pasteur maintained that yeast cells use oxygen when it is available and only switch to fermentation when oxygen is absent. So, perhaps Warburg was bound to conclude that the fermentation process he measured in cancer cells was, likewise, a response to an inadequate oxygen supply. He theorized that normal cells become cancerous only when their capacity for respiration is impaired.

Warburg’s interest in cancer arose at a moment when rates of cancer were rising around the world, not least in Germany. Scientists and doctors from many different countries began to theorize that cancer was a modern disease, a “disease of civilization.” In the first decades of the 20th century, many presented evidence that cancer was uncommon in populations that continued to eat the diets to which they had adapted over the eons. Could the cancer epidemic be due to modern Western diets, they wondered. By that time, studies of experimental animals had found that eating fewer calories, or fewer carbohydrates, could reduce rates of tumor growth. In 1913, two scientists from Cornell University reviewed these animal studies and reported that “when the diet includes carbohydrates the tumors grow luxuriantly.”

None of this evidence contradicts the role of the Warburg effect in the development of cancer. But the evidence, perhaps, suggests that Warburg, in his single-minded focus on oxygen and respiration, overlooked an important clue: the nutrients in the body in which a cancer develops can change “the soil” and make it more favorable for a cancer’s growth.

Hitler’s Cancer Obsession

If Warburg was in the right place, Berlin, by the early 1930s, it was no longer the right time for him. Warburg had two Jewish grandparents, making him a non-Aryan, at a moment when the Nazis were about to begin the most repugnant program of ethnic cleansing in recorded history. Would the non-Aryan Warburg survive if he remained in Germany?

The answer to that question produces another of the book’s intriguing themes. Apple suggests that Warburg likely survived only because Hitler, the most evil man of the 20th Century, had an abiding fear of cancer. Hitler had witnessed his mother’s death from breast cancer. A vegetarian with a life-long sugar addiction, Hitler suffered from chronic gastrointestinal upsets, which are perhaps not so uncommon in committed vegetarians. But his continual discomfort convinced Hitler that he, too, could be developing a terminal cancer.

Hitler appears to have believed that Warburg would discover a cure for cancer. And so, instead of being imprisoned, or, perhaps, much worse, Warburg was protected and continued his research in idyllic surroundings until the Russian forces approached Berlin from the East in April 1945.

By that point, Warburg’s brilliant career was already in decline. But there was even worse to come. In 1953, in a direct contradiction of Warburg’s hypothesis, the American scientist Sidney Weinhouse provided evidence that many cancer cells have a normal capacity for respiration. That same year, the discovery of the structure of DNA ushered in a completely new era of genetics-focused cancer research.Despite Warburg’s prodigious contributions to the understanding of cellular respiration, it appeared that the irresistible march of biological science had made Warburg and the entire field of cancer metabolism largely irrelevant.

This is where any book about Warburg might logically have ended. But Sam Apple did not spend five years researching and writing this book to bring it to such a sorrowful, pessimistic finish. The final 100 pages lift Ravenous from brilliant to exceptional.

Somehow, Apple must have sensed that there was more to the story, much more. But to uncover this deeper dimension would require that he develop yet another intellectual skill. He would have to become more than (just) a journalist divining an enthralling story from the published historical records. He would need to study, understand, and interpret the emerging field of modern cancer metabolism and then explain the field to his readers.

In so doing, Apple provides evidence that Warburg was constrained by the incomplete scientific knowledge of his day. Warburg made a hugely important discovery, and he was correct that most cancers turn to fermentation. But Warburg misinterpreted the true biological meaning of the Warburg effect, which, correctly stated, is that cancer cells have the intrinsic capacity to increase their production of lactic acid even in the presence of sufficient oxygen and normal respiration.

Warburg, in other words, had the science right but not necessarily the theory. But if impaired respiration is not the fundamental cause of the metabolic transformations seen in cancer, then what is?

How Cancer Cells Eat

Apple begins with a simple analysis of what Warburg had actually found: that the key characteristic of many cancer cells is that they “overeat” glucose.

Already in the 1800s, it was appreciated that cancers occur more commonly in those who are obese. As Frederick Hoffman, America’s leading cancer statistician wrote in 1937, “[O]verabundant food consumption unquestionably is the underlying cause of the root condition of cancer in modern life.” Animal experiments published in the 1940s also found that diets restricted in calories or in carbohydrates were associated with either less cancer or less cancer progression.

A possible biological explanation for these relationships would come only more recently and from an unexpected source: the discovery of the oncogenes. In 1997, researchers from Johns Hopkins discovered that one important oncogene activates lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), the key enzyme in the fermentation pathway, producing lactic acid. (Warburg himself had first isolated LDH in his studies seeking to explain the biological basis of the Warburg effect.) If oncogenes increase LDH activity in cancer cells, there could be a direct link between the fermentation pathway and the growth of malignant cancer cells.

The next bit of intriguing evidence was provided by one of the world’s most respected modern cancer researchers, Craig Thompson of the Memorial Sloan Kettering, who found that the oncogene AKT drives cancer by increasing the glucose uptake of cancer cells and switching on the Warburg effect.

In theory, the Warburg effect could simply be the result of unlucky mutations, which, in Thompson’s words, allow cancers to continue “gorging” on glucose. In this scenario, that cancer cells overeat glucose has nothing to do with our diets. But Apple convincingly argues that there is a connection between how we eat and how a cancer cell eats.

Apple next presents clear evidence that both obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) substantially increase one’s cancer risk. Both of these conditions are, in turn, firmly linked to insulin resistance, a condition in which blood insulin concentrations are perpetually elevated in the blood.

Are elevated levels of insulin, the hormone that tells our cells to consume glucose, possibly driving the Warburg effect and today’s epidemic cancer rates? Apple points out that excess insulin, which can function as a growth factor, is itself associated with many cancers and that many deadly cancers, including those of the prostate, uterus, breast, colon and lung, overexpress insulin receptors on their cell membranes. Some cancers will not even grow in a laboratory dish until insulin is added to the recipe.

And there is still more. Apple relates how, in the late 1980s, Lewis Cantley, now the director of the Meyer Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medicine, discovered another important oncogene, PI3K. This enzyme is directly activated by insulin and will drive Warburg metabolism. Mutations in the PI3K pathway have since been found to be the most common cancer mutations of all.

The Sugar Connection

The final two chapters of Ravenous complete the circle of Warburg’s contribution. Apple explains that Emil Fischer was Warburg’s first teacher and most revered inspiration. Fischer revolutionized the understanding of carbohydrate structure, establishing the differences between two common carbohydrate building blocks, glucose and fructose. When combined, fructose and glucose produce sucrose, or common table sugar.

It was long thought that the fructose half of sugar (sucrose) was harmless because it did not cause a sharp increase in blood sugar or lead to a damaging hyperinsulinemic response.

We now understand this rather differently. While glucose will raise blood glucose and insulin concentrations and is therefore undesirable for those with insulin resistance, fructose, the other half of sugar, is perhaps even more harmful. Because much of the fructose we consume is metabolized directly to fat in the liver—where it becomes a key driver of a novel alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)—it can dramatically worsen insulin resistance in humans, leading to higher and higher insulin levels.

In the two concluding chapters, Apple advances the theory that sugar (including the specific harmful effects of fructose) is the key, but still largely overlooked, nutritional driver of obesity and cancer. Apple is not the first to link the dramatic increase in sugar consumption over the past 150 years to rising rates of cancer. But he is the first to gather all of the evidence in one place: a book, Ravenous, that succeeds on every level.