This year, we celebrate the 34-year anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act being signed into law. But I am embarrassed to admit that I have no idea how to provide care to patients with disabilities.

As a physician-in-training, I am challenged to learn every aspect of medicine and demonstrate mastery of what is considered best medical practice. We learn to take patients’ medical histories, carry out physical exams, and develop appropriate assessments and plans. We learn to put the patients at ease and build trust through empathy, open communication, and compassion.

After I began working with patients with disabilities, however, I realized that I did not know how to treat them, let alone make them feel at ease. Medical educators must do a better job at building a curriculum that adequately prepares physicians to meet the complex needs of patients with disabilities.

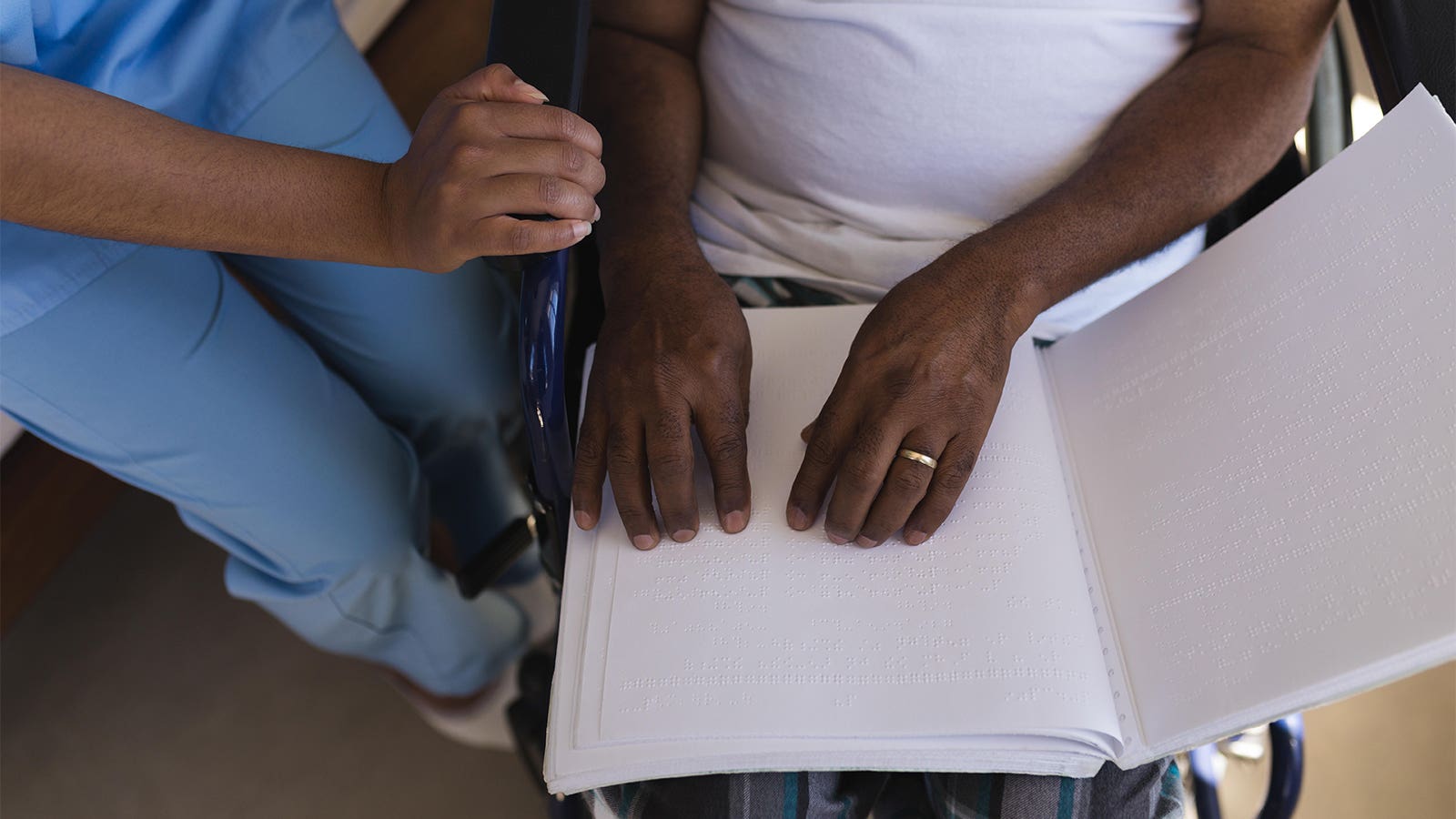

As a Schweitzer Fellow, I worked with blind adults and adults with visual impairments living in a community home. In this setting, more than 90{e60f258f32f4d0090826105a8a8e4487cca35cebb3251bd7e4de0ff6f7e40497} of residents live with multiple diseases, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cardiovascular disease, which are managed by medications. On average, these residents take more than nine medications, administered by the onsite nursing team.

Where are the doctors who prescribed them, you might ask? Well, they are nowhere to be found. Some residents make the effort to see their primary care physician (PCP), but they often report that they are not treated with respect. Despite efforts to coordinate transportation plans with appropriate accommodations, residents often find themselves being asked to reschedule due to unforeseen conflicts when they arrive at their PCP’s clinic. When they are seen by their PCP, it is not uncommon for them to navigate office visits or undergo physical exams without proper accommodations, such as a larger exam room to accommodate patients with wheelchairs or examination tables with adjustable height. In one case, I was horrified to hear from a patient that their PCP screamed at them for not following instructions. These experiences are consistent with those reported in literature on healthcare perceptions by patients with disabilities, who express that they feel “frustrated, confused … invisible, or viewed as incompetent.”

The CDC reports that approximately 61 million U.S. adults live with some disability — and the numbers are growing. According to the World Health Organization, an estimated 1.3 billion people globally live with a form of disability. With an aging population, experts anticipate that more adults will lose their vision and/or hearing. When we also consider social and health disparities, risks for developing multiple medical conditions increase significantly for adults with disabilities. Moreover, a 2007-2019 study found that all-cause mortality was nearly twice as high for adults with disabilities versus those without disabilities. With this changing patient landscape and compromised outlook, we need more programs to educate and prepare physicians to provide better care.

To address this gap, the American Medical Association encourages medical schools to establish elective rotations specializing in care for people with disabilities. My medical school created an elective designed to teach physicians-in-training to specialize in care for the disability community. The curriculum focuses on interprofessional communication and offers an opportunity to engage directly with patients who have disabilities. Students learn about the causes of intellectual/developmental disabilities, gain patient perspective, and demonstrate clinical skills through an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE).

Courses like this prepare us to better serve patients with disabilities and supplement our core clinical skills. I eagerly look forward to taking this course in my last year of training. But all medical schools should offer more classes like this, as well as classes specific to particular populations of people with disabilities. Without them, students are more likely to perform poorly and inadequately place orders on clerkship OSCE for patients with disabilities. Every medical trainee should at least have a foundation for care specific to people with disabilities by the time they graduate.

The disability community is often overlooked. To address this, more physicians should also become advocates for patients with disabilities. While some medical schools already have a curriculum designed for serving patients with disabilities, a majority of U.S. medical schools do not. Medical schools should expand their efforts to educate physicians and physicians-in-training.

Simon Park, PhD, is a third-year medical student at the Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine. He is also a Chicago Area Schweitzer Fellow, a year-long service-learning initiative supported by the Health & Medicine Policy Research Group; fellows design and implement innovative projects that address the health needs of underserved Chicago communities.